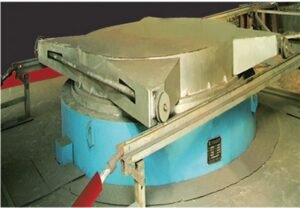

In the plant, I often see people chase output by pushing roller pressure up. Then the mill starts to vibrate, the sleeve temperature rises, and the wear pattern turns ugly. The problem is simple. Pressure changes the whole failure mode. If I choose material by habit, I pay for it with cracks, spalling, and early shutdowns.

Roller pressure sets the contact stress, heat, and fatigue load on the sleeve surface, so it decides whether I should prioritize hardness, toughness, or a composite structure. When pressure goes up, abrasive and fatigue wear rise fast, and the “safe” high-chrome choice often becomes the risky choice.

I learned this the hard way. I once watched a sleeve that looked “hard enough” fail early because it was not tough enough for the real pressure spikes. After that, I stopped asking only “how hard is it?” and started asking “what does pressure do to my surface and my core?”

Why does higher roller pressure accelerate wear on my grinding components?

Higher pressure is not just “more force.” It changes what happens at the contact line. If I do not respect that, wear climbs fast and failures come earlier than the plan.

Under higher roller pressure, contact stress increases. That pushes the surface into plastic deformation if hardness is not high enough. Then the surface roughens, and the abrasive particles cut deeper. Pressure also increases real contact area at micro-level, so adhesive wear can rise. On top of that, the cyclic load becomes heavier, so fatigue wear moves to the front. Once fatigue starts, I see micro-cracks, then crack links, then spalling.

When I break it down for a maintenance team, I use a simple map. Pressure decides which wear mode dominates, and that decides the material.

| Roller pressure level (relative) | Main wear risk I see first | What I need from material first | Common surface symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Mild abrasion | Basic hardness + stable microstructure | Smooth polishing wear |

| Medium | Abrasion + local adhesion | Higher hardness + lower friction | Grooves + shiny adhesion patches |

| High | Fatigue + spalling | High compressive strength + toughness + hard phase | Network cracks + flakes |

| Extreme | Rapid fatigue + thermal softening | Composite/graded design + heat stability | Hot spots + deep spalls |

In my experience, once pressure crosses into “high,” I stop trusting simple steels. I start looking for a system that can carry load, resist cutting, and stop crack growth at the same time.

How do I choose the right roller sleeve material for different pressure levels?

Choosing by pressure is really choosing by stress and fatigue. If I match material to pressure band, I reduce surprises and I can plan shutdowns.

I match low pressure with cost-effective wear alloys, medium pressure with improved hard-phase systems, and high pressure with composite or graded structures that keep hardness at the surface and toughness in the body. The goal is not maximum hardness. The goal is stable wear without cracks.

Here is the way I do it on site. I start with pressure, then I add feed abrasiveness, moisture, and vibration history. Then I pick a material “family.”

| Pressure band | Material direction that usually works | Why it fits pressure loading | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High-chrome iron or standard wear steel | Enough hardness for light stress | Can still crack if vibration is high |

| Medium | Optimized high-chrome / carbide-reinforced alloys | Better abrasion resistance as stress rises | Needs good casting quality, avoid coarse carbides |

| High | Metal-ceramic composite / carbide-ceramic reinforced composite | Hard surface carries abrasion, tough matrix slows cracks | Requires correct composite design, not just “hard inserts” |

| Extreme | Graded composite or engineered composite layer + tough backing | Balances surface hardness and core toughness under fatigue | Needs proven design and process control |

I also keep one rule: if pressure is high and the mill shows pressure spikes, I prioritize toughness and fatigue resistance first, then I add hardness. That one rule prevents many spalling events.

What happens if my roller sleeve material cannot withstand my mill pressure?

When material is under-designed for pressure, the mill does not fail in a polite way. It fails in a way that steals production time.

If hardness is too low, I see plastic deformation, rapid profile loss, and uneven wear. That causes vibration, then the contact becomes worse, then wear accelerates again. If toughness is too low, I see cracks at the surface, then cracks grow under cyclic load, then spalling starts. Once spalling begins, the surface becomes rough, and the bed becomes unstable. The mill draws more power, and the operator increases pressure to recover. That makes the damage faster.

I explain it as a chain reaction:

| Weak point in material | First symptom | Next step | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low hardness | Flattening / smeared surface | Deep grooves + uneven wear | Fast wear-out + vibration |

| Low toughness | Fine surface cracks | Crack linking | Spalling + chunks loss |

| Poor fatigue resistance | Subsurface micro-cracks | Repeated flaking | Short intervals + unstable grinding |

| Low heat stability | Softening at hot spots | Adhesion + tearing | Sudden wear jump |

This is why I do not accept “it worked before” as proof. If the plant raised roller pressure, the old proof is gone.

How does metal ceramic composite perform under high roller pressure?

High pressure punishes materials that are only hard or only tough. A metal-ceramic composite can survive because it spreads the job across phases.

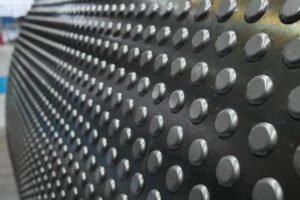

Under high roller pressure, metal-ceramic composite keeps a hard wear surface to resist cutting, while the metal matrix provides toughness and load support to slow crack growth. Done right, it also avoids large brittle zones that trigger spalling.

When I look at performance under pressure, I care about three things: contact stress, fatigue cycles, and crack arrest. A good composite gives me a hard phase to take abrasion, and a tougher phase to stop cracks. It can also be designed as graded, so the surface is harder and the inside is tougher. That matters because the surface sees wear, but the body sees bending and shock.

| What pressure does | What composite feature helps | What I expect to improve |

|---|---|---|

| Raises cutting depth | Hard ceramic/carbide phase | Lower abrasive wear rate |

| Raises fatigue load | Tough metal matrix support | Less spalling and flaking |

| Raises crack risk | Crack-deflection and crack-bridge paths | Slower crack growth |

| Raises heat | Heat-stable phases | More stable hardness |

In Dafang-Casting projects, I focus on keeping the ceramic phase stable and well bonded, because high pressure is where weak bonding shows up first.

Why do traditional high chromium rollers fail under high pressure?

High-chrome iron is a strong abrasion fighter, but pressure turns the battle into fatigue and cracking. That is where it can lose.

Traditional high chromium rollers rely on hard carbides in a brittle matrix. Under high roller pressure, the cyclic load drives micro-cracks at carbide-matrix interfaces and at brittle zones. Once cracks start, they grow fast because the material has limited toughness. If the casting has coarse carbides or segregation, the crack path becomes even easier. Under pressure spikes, I often see surface cracking, then spalling, even if average wear rate looked fine.

This is the pressure problem in one table:

| Property | High-chrome roller strength | High-chrome roller weakness under pressure |

|---|---|---|

| Abrasion resistance | High | Can still spall and lose chunks |

| Toughness | Medium to low | Cracks grow fast under cyclic load |

| Fatigue resistance | Limited in brittle zones | Flaking and spalling dominate |

| Sensitivity to defects | High | Porosity/segregation becomes crack starters |

So I do not call high-chrome “bad.” I call it “pressure-limited.” If pressure is high, I shift to designs that fight fatigue, not only abrasion.

How can proper material selection reduce cracking under roller pressure?

Cracking under pressure is not solved by hardness alone. Cracking is solved by controlling stress, stopping crack start, and slowing crack growth.

I reduce cracking by choosing a sleeve with enough toughness and fatigue resistance for pressure spikes, and by using a structure that keeps hard phases fine and well supported. In many mills, that means moving from monolithic alloys to composite or graded solutions.

In practice, I look for these design signals:

| What I check | Why it matters under pressure | What I prefer |

|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength | High pressure is compressive load | High compressive strength base |

| Toughness | Stops crack growth | Tough matrix, not brittle bulk |

| Hard phase size and distribution | Coarse hard phases crack easier | Fine, well distributed reinforcement |

| Bonding quality | Weak interfaces open under load | Strong metallurgical bonding |

| Graded structure | Surface needs hardness, core needs toughness | Hard outside, tough inside |

I also remind teams that pressure spikes from unstable bed can crack any material. Material selection reduces risk, but stable operation finishes the job.

Does roller pressure influence service life and cost per ton for my mill?

Yes, and it often does it in a way that is not linear. A small pressure increase can cut life much more than people expect.

Higher pressure increases wear rate and fatigue damage per hour. That shortens service intervals. Then shutdown frequency rises. Then the real cost per ton climbs because downtime is expensive. Even if a cheaper sleeve has a lower unit price, it can cost more per ton if it forces extra shutdowns or causes vibration damage to other parts.

I like to show it with a simple cost-per-ton view:

| Item | Low pressure case | High pressure case |

|---|---|---|

| Wear rate | Lower | Higher |

| Failure mode | Wear-out | Spalling/crack-out |

| Planned shutdowns | Fewer | More |

| Risk cost | Low | High |

| Best material strategy | Lowest cost alloy that is stable | Highest stability material, even if unit price is higher |

This is why I treat “replaceability” as part of selection. At high pressure, I want predictable life more than I want the lowest purchase price.

How can I match roller pressure with wear resistance and toughness?

Pressure forces a trade-off. If I chase wear resistance only, I can get a brittle sleeve. If I chase toughness only, I can get fast wear. The match is balance.

I match roller pressure by selecting a material system that has high surface hardness for abrasion and enough bulk toughness and fatigue resistance to prevent cracking and spalling. At high pressure, I prefer composite or graded designs that do both jobs.

I use this decision guide:

| Pressure condition | What I prioritize first | What I avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Stable, moderate pressure | Hardness + uniform wear | Overly tough low-hardness alloys |

| High pressure, stable bed | Hardness + compressive strength | Brittle high-carbide structures |

| High pressure, unstable bed | Toughness + fatigue resistance | “Hard only” materials |

| Extreme pressure | Composite/graded structure | Thin coatings as the only solution |

I also watch for adhesive wear and galling at high pressure. If the friction is high, I choose systems that reduce friction and resist adhesion, not just higher hardness.

How do I optimize roller pressure and material selection for stable mill operation?

If I want stable operation, I cannot treat pressure and material as two separate knobs. They work as one system. A better sleeve can allow safer pressure. Better pressure control can allow simpler materials. The best result is a stable grinding bed and predictable wear.

I optimize by setting roller pressure for bed stability first, then selecting a sleeve material that matches the real peak pressure and fatigue cycles, not only the average pressure. This reduces vibration, cracking, and surprise shutdowns.

This is the practical workflow I use:

| Step | What I do | Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check actual pressure profile, including spikes | Spikes drive cracks more than averages |

| 2 | Review vibration history and wear pattern | Tells me dominant wear mode |

| 3 | Decide target failure mode: wear-out, not crack-out | Predictable maintenance |

| 4 | Select material family by pressure band | Aligns hardness, toughness, fatigue strength |

| 5 | Tune pressure for stable bed and lower spikes | Reduces fatigue and heat |

| 6 | Track service life and cost per ton after change | Confirms true improvement |

I also keep a hard rule: if the mill needs extreme pressure to stay productive, it often means the grinding condition is not stable. Fixing stability can be cheaper than buying the most exotic sleeve every time.

Conclusion

Roller pressure decides contact stress, heat, and fatigue loading, so it decides my wear material strategy. As pressure rises, abrasion is only part of the story, and cracking and spalling become the real risk. I get the best results when I match pressure level and pressure spikes with a material that balances surface hardness and core toughness. When pressure is high, I often choose metal-ceramic composite from Dafang-Casting because it keeps wear resistance while also fighting fatigue damage, so the mill stays stable and costs per ton drop.