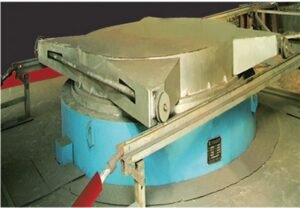

In my mills, I have seen the same painful pattern. A roller sleeve looks “fine” at install, then wear climbs fast, vibration starts, and a shutdown comes early. Most people blame the hardfacing, the feed, or the operator. Many times, the real problem sits deeper: the composite layer thickness is not matched to the load and impact in the VRM.

Composite layer thickness affects service life because it controls how much wear volume you have, how well the sleeve carries load, and how cracks start and grow. Too thin wears through early and exposes weaker backing metal. Too thick can raise residual stress and cracking risk. The best thickness is a working range, not a single number.

I want to make this simple. Thickness is not only “more material to wear away.” It also changes stiffness, stress paths, and how impact energy spreads. If I get the thickness wrong, the sleeve can fail in a new way even if the material recipe is good. So I always treat thickness like a design lever, not a sales parameter.

What is the ideal composite layer thickness for my VRM roller sleeve?

When I choose thickness, I do not chase the thickest layer. I chase the thickness that matches my wear rate and my crack risk in the same campaign.

The ideal composite layer thickness is the range that provides enough wear allowance and load support without driving high residual stress or brittle cracking. In practice, I size it by: expected wear depth per campaign, impact level, operating pressure, and how stable the mill is.

In the field, I start from three questions: how fast does the surface wear, how often do impacts happen, and how much margin I need before I reach the substrate. Thickness raises load-bearing capacity because a thicker composite zone is stiffer and spreads contact stress deeper into the sleeve body. It also delays crack initiation and slows crack growth under cyclic loading, but only up to a point. After that point, the added thickness brings smaller life gains and can add thermal and shrinkage stress from manufacturing and from hot-cold operation. I also watch thickness uniformity. Small local thin spots become stress concentrators and become the first places to pit, spall, or crack.

| What I size for | What thickness changes | What I watch in operation |

|---|---|---|

| Wear allowance | More volume before substrate exposure | Hardness drop and wear acceleration |

| Load support | Higher stiffness, less local plastic strain | Vibration trend and pressure stability |

| Crack behavior | Longer path and slower growth | Edge cracks and heat-check patterns |

| Residual stress | Can rise with thickness | Early cracks after thermal cycling |

Why does insufficient composite thickness cause premature wear in my mill?

I have seen thin composite layers look great for a short time, then fail fast. The failure feels sudden, but the setup was already wrong.

Insufficient thickness causes premature wear because the protective composite zone is consumed too quickly, then the backing metal takes load and wear it cannot handle. That shift raises wear rate, heat, and local deformation.

A thin composite layer has less wear volume, so the mill reaches the transition zone earlier. Once the surface gets close to the interface, stresses change. The contact pressure no longer sits inside a thick wear layer. It pushes into the tougher but softer support metal. Then wear turns from steady micro-abrasion into a mix of abrasion, plastic flow, and micro-spalling. This is where I often see uneven wear bands, local hot spots, and faster vibration growth. Under cyclic loading, thin layers can also crack sooner because the stress intensity at a small defect rises faster when the remaining protective thickness is low. Even if the composite itself is strong, it simply runs out of “room” to protect the sleeve.

| Stage in campaign | Thin layer behavior | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Early hours | Looks normal, wear rate seems acceptable | False confidence |

| Mid hours | Interface effects start, stress redistributes | Wear accelerates |

| Late hours | Substrate exposure and plastic deformation | Spalling, vibration, shutdown |

Can an overly thick composite layer increase cracking risk in my roller sleeve?

Yes. I have learned this the hard way. Some sleeves fail not because they wear out, but because they crack before the wear layer is used.

An overly thick composite layer can increase cracking risk because it can raise residual stresses from thermal gradients and shrinkage, and it can increase interlayer shear stress during bending and impact. Those stresses can trigger cracks even when wear is still low.

Thickness increases stiffness, and that sounds good, but stiffness also means less compliance under load. If the mill sees impact, the composite layer can carry higher peak stress instead of sharing it smoothly with the support metal. During manufacture and heat cycles, a thick composite zone can trap thermal gradients. That can leave tensile residual stress at the surface or near the interface. In service, those stresses add to operating stress. If the layer also has a high ceramic fraction, cracks can start at pores, ceramic clusters, or sharp transitions. I also pay attention to interlaminar or interface stress. A thick layer can raise shear stress at the boundary when the sleeve flexes. That can lead to interface cracking, then spalling.

| Risk driver | Why thick layers can worsen it | What I do to control it |

|---|---|---|

| Residual tensile stress | More gradient, more shrinkage restraint | Controlled cooling, graded structure |

| Interface shear | Higher bending mismatch | Transition zone design, better bonding |

| Brittle crack start | Higher peak stress at defects | Toughened matrix, defect control |

| Thermal cycling | Repeated expansion mismatch | Match CTE, reduce sharp property jumps |

How do I balance wear resistance and toughness through composite layer design?

I never treat wear resistance and toughness as enemies. I treat them as a trade I can shape with thickness, gradient, and structure.

I balance wear resistance and toughness by using enough thickness for wear allowance while keeping stress and impact behavior stable through a graded composite design, not a sudden hard layer on a soft base.

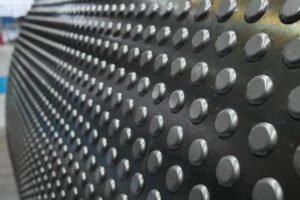

If I make the whole layer extremely hard, I may win on abrasion but lose on cracking and spalling. If I make it too tough, I may survive impact but wear too fast. Thickness controls the “budget” for wear, but the internal structure controls how cracks behave. I prefer a design where the surface zone is optimized for abrasion and micro-cutting resistance, while the deeper zone is more supportive and crack-tolerant. A graded ceramic distribution can reduce stress jumps and lower the chance that a crack runs straight through. Thickness uniformity also matters. If thickness varies, the thin areas become the weak link. In my experience, good thickness control plus a proper transition zone often beats simply adding more millimeters.

| Design lever | Improves wear | Improves toughness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| More thickness | ✅ | ⚠️ | Helps until stress becomes the limiter |

| Graded ceramic fraction | ✅ | ✅ | Reduces stress concentration |

| Toughened matrix | ⚠️ | ✅ | Helps impact and crack bridging |

| Smooth transition zone | ⚠️ | ✅ | Protects interface under bending |

| Uniform thickness control | ✅ | ✅ | Reduces local overstress |

How does composite thickness influence impact resistance under my working conditions?

Impact is where many “hard” solutions fail. I always ask where the impact comes from: metal tramp, feed lumps, unstable bed, or start-stop events.

Composite thickness influences impact resistance by changing how impact energy spreads and how deep the high-stress zone goes. A moderate increase often improves damage tolerance, but excessive thickness can raise interface shear and cracking under repeated shocks.

With more thickness, the layer can act like a stronger load-bearing plate, so the peak contact stress drops and the damage zone can become broader but less severe. This can delay crack initiation and slow propagation. Still, impact resistance is not only thickness. If the layer becomes too stiff compared to the base, the sleeve can behave like a hard shell on a softer core. Under shock, that mismatch can drive cracks at the interface or cause surface chipping. I have also seen cases where thicker layers reduced fatigue life because they raised cyclic shear stress near the interface. So I match thickness with bed stability. If the mill has frequent impacts, I lean toward a tougher gradient and controlled thickness rather than maximum thickness.

| Working condition | Thickness direction I prefer | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Stable bed, high abrasion | Slightly thicker | Use wear allowance efficiently |

| Frequent impact, tramp events | Moderate thickness + tough gradient | Reduce chipping and interface stress |

| Strong thermal cycling | Avoid excessive thickness | Lower residual and thermal stress |

| High vibration history | Prioritize uniformity | Thin spots trigger local failure |

Is the optimal composite layer thickness different for cement, coal, and raw mills?

Yes, and I never use one thickness logic across all three. The wear mechanism changes, and the impact pattern changes.

Optimal thickness differs by application because cement and slag grinding are more abrasive, coal mills often have different impact and erosion patterns, and raw mills can vary widely with moisture and feed hardness. Each case shifts the best thickness range.

In cement finish grinding and slag conditions, abrasive minerals and high pressure can drive steady wear and micro-spalling, so I often need more wear allowance and strong surface hardness. In coal mills, I often worry more about erosion, foreign objects, and operational swings. Coal ash chemistry can also change surface behavior. Raw mills are the most mixed. Limestone, clay, sand, and additives can change quickly, and moisture can destabilize the bed and raise vibration. So the “best thickness” is not a fixed value. It is a response to wear depth per campaign plus the risk of cracking. I also consider maintenance strategy. If a plant plans to rework at a certain interval, I size thickness to match that planned stop rather than chasing maximum possible life.

| Tipo di mulino | Main wear drivers I see | Thickness focus |

|---|---|---|

| Cement / slag | High abrasion, high pressure, micro-spalling | Wear allowance + surface integrity |

| Coal | Erosion, tramp, swings in operation | Toughness + controlled stiffness |

| Raw | Mixed abrasion, moisture effects, unstable bed | Uniformity + balanced gradient |

How does metal ceramic composite thickness improve my cost per operating hour?

Plants do not buy thickness. They buy hours. I always translate thickness choices into cost per operating hour.

Composite thickness improves cost per operating hour when it extends stable operating time more than it increases sleeve cost and downtime risk. The best thickness lowers total shutdown frequency and protects the mill from secondary damage.

If I add thickness and gain more hours, the cost per hour drops only if the sleeve still runs stably. If thicker layers raise crack risk and cause an early stop, cost per hour gets worse. That is why the relationship is nonlinear. Often, service life increases quickly when I move from too thin to a good range. Then life gains slow down. Past that, life may even drop if cracks become the failure mode. I also include indirect costs. When a sleeve wears through early, I often see more vibration, more grinding inefficiency, and risk to the table liner and bearings. Extending life by the right thickness can protect other parts and lower the true total cost.

| Cost element | How correct thickness helps | Typical mistake |

|---|---|---|

| Sleeve replacement cost | Fewer replacements | Overpay for thickness that adds little |

| Downtime cost | Longer campaign, planned stops | Unplanned stop from cracking |

| Energy cost | More stable grinding bed | Vibration and poor grinding efficiency |

| Secondary damage | Protects table and internals | Wear-through exposes base metal |

What happens to my roller sleeve when the composite layer wears unevenly?

Uneven wear is a warning light. I treat it like a symptom of stress, feeding, or thickness uniformity problems.

When the composite layer wears unevenly, local thickness becomes too thin in bands or spots, which raises contact stress and triggers faster wear, heat, vibration, and crack initiation. The sleeve can then fail early even if average wear looks acceptable.

Uneven wear changes the load distribution across the roller. That drives a feedback loop. The thin area carries more stress, so it wears faster. The bed becomes less stable, so impact rises. Then micro-cracks start at the thin zone because stress concentration is higher. If the composite thickness is also non-uniform from manufacturing, the same thin spots become the first failure points. I have seen sleeves where the “average remaining thickness” still looked okay, but one sector was already near the interface and started spalling. That is why I track profile and vibration trend, not only total tonnage.

| Symptom | What it usually means | What it can lead to |

|---|---|---|

| Wear bands | Bed instability or misalignment | Local overheating, spalling |

| One-side wear | Skew load or process imbalance | Vibration, bearing stress |

| Patchy pitting | Defects or chemical effects | Crack start points |

| Step at interface | Layer consumed locally | Rapid failure after exposure |

How can I customize composite layer thickness for my mill to maximize service life?

Customization is where I see the biggest gains. I do not start with thickness. I start with failure history and the operating window.

To customize thickness, I match the composite wear allowance and stiffness to your real wear depth, pressure, impact frequency, and thermal cycling, then I lock in uniform thickness and a graded transition so the failure mode stays wear-dominated, not crack-dominated.

I collect three types of data from the last campaign: wear profile, crack or spall locations, and operating events like vibration spikes and tramp incidents. Then I select a thickness range that covers expected wear plus a safety margin, but I do not push thickness so far that residual stress dominates. After that, I tune the internal structure. A thicker surface zone is not enough if the interface is weak or if stiffness jumps too fast. I prefer a controlled gradient so stress flows smoothly into the backing metal. I also specify thickness tolerance and inspection points because uniformity is a life factor by itself. Finally, I align the design with maintenance. If the plant runs planned stops, I design thickness to hit that stop with stable performance.

| Input I ask for | What I change in the sleeve | Perché è importante |

|---|---|---|

| Wear depth per campaign | Total composite thickness | Ensures wear allowance matches reality |

| Impact history | Toughness gradient and transition | Prevents chipping and interface cracks |

| Thermal cycles | Limit excessive thickness, match expansion | Reduces residual and thermal stress |

| Wear profile shape | Uniformity targets and profile control | Stops local thin-spot failure |

| Maintenance plan | Thickness margin strategy | Optimizes cost per operating hour |

Conclusione

In my experience, composite layer thickness decides whether my roller sleeve fails by normal wear or by early cracking and spalling. Thin layers run out of protection and trigger fast wear after the interface. Overly thick layers can trap stress and crack early. The best result comes from a matched thickness range, strong uniformity control, and a graded metal-ceramic design. At Dafang-Casting, I use this approach to help mills run longer, with lower downtime and lower cost per operating hour.